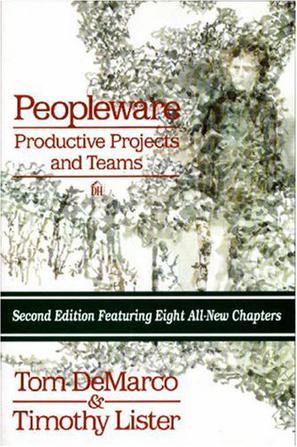

Summed up in one sentence, Peopleware says this: give smart people physical space, intellectual responsibility and strategic direction. DeMarco and Lister advocate private offices and windows. They advocate creating teams with aligned goals and limited non-team work. They advocate managers finding good staff and putting their fate in the hands of those staff. The manager's function, they write, is not to make people work but to make it possible for people to work.

Why is Peopleware so important to Microsoft and a handful of other successful companies? Why does it inspire such intense devotion amongst the elite group of people who think about software project management for a living? Its direct writing and its amusing anecdotes win it friends. So does its fundamental belief that people will behave decently given the right conditions. Then again, lots of books read easily, contain funny stories and exude goodwill. Peopleware's persuasiveness comes from its numbers - from its simple, cold, numerical demonstration that improving programmers' environments will make them more productive.

The numbers in Peopleware come from DeMarco and Lister's Coding War Games, a series of competitions to complete given coding and testing tasks in minimal time and with minimal defects. The Games have consistently confirmed various known facts of the software game. For instance, the best coders outperform the ten-to-one, but their pay seems only weakly linked to their performance. But DeMarco and Lister also found that the best-performing coders had larger, quieter, more private workspaces. It is for this one empirical finding that Peopleware is best known.

(As an aside, it's worth knowing that DeMarco and Lister tried to track down the research showing that open-plan offices make people more productive. It didn't exist. Cubicle makers just kept saying it, without evidence - a technique Peopleware describes as "proof by repeated assertion".)

Around their Coding Wars data, DeMarco and Lister assembled a theory: that managers should help programmers, designers, writers and other brainworkers to reach a state that psychologists call "flow" - an almost meditative condition where people can achieve important leaps towards solving complex problems. It's the state where you start work, look up, and notice that three hours have passed. But it takes time - perhaps fifteen minutes on average - to get into this state. And DeMarco and Lister that today's typical noisy, cubicled, Dilbertesque office rarely allows people 15 minutes of uninterrupted work. In other words, the world is full of places where a highly-paid and dedicated programmer or creative artist can spend a full day without ever getting any hard-core work. Put another way, the world is full of cheap opportunities for people to make their co-workers more productive, just by building their offices a bit smarter.

A decade and a half after Peopleware was written, and after the arrival of a new young breed of IT companies called Web development firms, it would be nice to think DeMarco and Lister's ideas have been widely adopted. Instead, they remain widely ignored. In an economy where smart employees can increasingly pick and choose, it will be interesting to see how much longer this ignorance can continue.

Tom DeMarco和Timothy Lister是大西洋系统协会(www.atlsysguild.com)的负责人。从1979起,他们就在一起演讲,写作和从事国际性的咨询工作,主要涉及软件工程、生产力、估算、管理学和公司文化。 Tom DeMarco的职业生涯开始于贝尔实验室,他是结构化分析和设计的创始人之一,之后,他转向研究软件开发中的管理及其方法。他由于“对信息科学的重大贡献”成为1986年的J.-D. Warnier奖的得主。DeMarco总共已出版了六本书,其中项目管理小说《最后期限》(已由清华大学出版社出版)曾被评为亚马逊网上书店和巴诺书店的最佳畅销书。Timothy Lister的研究领域主要集中在对软件组织和项目的风险管理。Tim也为美国仲裁协会工作,负责解决软件争端。他还是美国国防部下设的软件程序经理网络的航空理事会员。

Peoplewaretxt,chm,pdf,epub,mobi下载

Peoplewaretxt,chm,pdf,epub,mobi下载 首页

首页

很好。挺不错的。

五星推荐

相当发人深省

有深度